18.06.2025

In this article, Molly Yau looks at the Edwards vs Meril case at the Unified Patent Court (UPC), and explores its procedural implications. Molly draws on her academic background and long-standing interest in cardiovascular devices to introduce key technical details of the case - which relates to implantable prosthetic heart valves and delivery systems - and highlights the decision’s significance for UPC practice.

Thank you

On 4 April 2025, the UPC Local Division Munich issued a decision on the Edwards vs Meril case. Notably, the Court emphasised the importance of their now standardised approach for assessing claim interpretation and proposed that the UPC should be clear in its adoption of the well-known European Patent Offices (EPO’s) problem-solution approach (PSA) for assessing inventive step.

Summary of the Dispute

Edwards Lifesciences Corporation (“Edwards”) filed an infringement action against Meril Life Sciences PVT Ltd, Meril GmbH and Meril Italy S.r.r. (collectively “Meril”), alleging that Meril’s prosthetic heart valve – sold in Germany – infringed the granted claims of Edward’s European patent (EP 3 669 828 B2) registered with unitary effect. Meril contested the alleged infringement and filed counterclaims for revocation arguing that the patent was invalid in its entirety. The oral hearing before the division took place in Munich on 11 February 2025.

The Invention

To provide some context, the patent at issue (owned by Edwards), relates to an implantable prosthetic heart valve with a small crimped diameter, having sufficient safety, reliability and longevity.

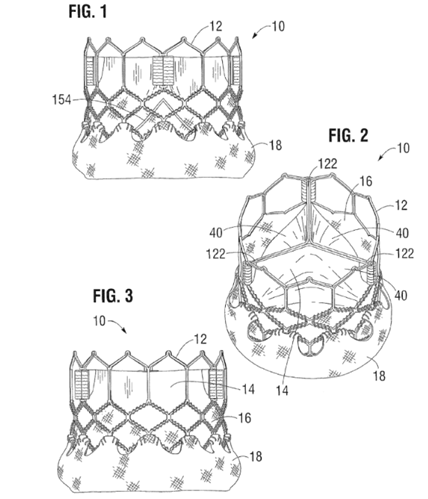

The valve comprises a number of leaflets and a tricuspid configuration to mimic the construction of a natural heart valve which can be seen in the figures below. The leaflet structure (14) is secured to a frame of the valve by primary (116) and secondary (122) tabs of the leaflets. The secondary tabs (122) comprise an inner (142) and outer (144) portion which are subject to folding, constituting a critical feature of the invention.

Figures 1 to 3 taken directly from EP 3 669 828 B2.

“An implantable prosthetic heart valve (10), comprising:

an annular frame (12) comprising a plurality of leaflet attachment portions (30); and

a leaflet structure (14) positioned within the frame (12) and secured to the leaflet attachment portions (30) of the frame (12), the leaflet structure (14) comprising a plurality of leaflets (40), each leaflet comprising a body portion, two opposing primary side tabs (116) extending from opposite sides of the body portion, and two opposing secondary tabs (112) extending from the body portion adjacent to the primary side tabs (116);

characterised in that the secondary tabs (112) are folded about a radially extending crease such that a first portion (142) of the secondary tabs (112) lies flat against the body portion of the respective leaflet (40), and the secondary tabs (112) are folded about an axially extending crease such that a second portion (144) of the secondary tabs (122) extends in a different plane than the first portion (142).

Meril submitted that the leaflets having a “substantially V-shaped intermediate edge portion” was a necessary feature for achieving the overall aim of the patent. Therefore, interpreting the ‘body portion’ of each leaflet as necessarily being ‘V-shaped’, i.e. limiting its literal meaning. Edwards, on the other hand, submitted that a V-shape of the body portion of the leaflet is irrelevant to the function of the invention. Thus, concluding that a limitation of the term “body portion” of the leaflet, as indicated by Meril, cannot be inferred from the wording of the claims, description or drawings.

“with regard to the arguments presented in this case, it must be emphasised that a narrowing construction of a broader claim language on the basis of the description and drawings should be allowed in exceptional cases”

With this in mind, the Court disagreed with Meril, arguing that the presence of the V-shaped leaflets is purely optional and not mandatory. They further noted that Claim 1 does not further specify the shape of the body portion of a leaflet and so broadly refers to valves with leaflets of any shape.

Interestingly, when it came to the inventive step assessment, the Court stated that the Problem-Solution Approach (PSA) developed by the EPO shall primarily be applied and set out the well-recognised elements of the PSA: stating a technical problem, solution and person skilled in the art.

This is a noteworthy point because the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal of the UPC have assessed inventive step using different approaches across various decisions. Some rulings explicitly refer to the PSA, while have others applied a different approach, adopting tests similar to the assessment of inventive step used by the German Federal Court of Justice. Although both approaches should, in practise, lead to the same outcome if applied correctly, the court stated:

"this Panel takes the decision to apply the PSA as practiced by the EPO, including and the BoAs, to the extent feasible and to state this explicitly as there is a need for legal certainty for both the users of the system and the various divisions of the Unified Patent Court. Applying the PSA further aligns the jurisprudence of the Unified Patent Court with the jurisprudence of the EPO and the BoA."

Under this approach, both parties agreed that the skilled person is a team, comprising a medical device engineer and an interventional cardiologist. While Meril argued that the team would further include a cardiac surgeon, the Court deemed this unnecessary.

Meril argued that there was no technical effect resulting from the distinguishing features of the patent in suit and thus formed the objective technical problem as providing an alternative configuration of the secondary tab. On this basis, Meril argued that the skilled person would be motivated to adapt the configuration in a manner anticipated by Claim 1 of the patent in suit.

However, Edwards argued that the objective technical problem to be solved, based on the same distinguishing features, is improving valve reliability, durability and safety, which is achieved as a result of a smaller crimp profile of the valve. Edwards further argued that the person skilled in the art would have no motivation to modify the valve. And with respect to the proposed modification, Edwards submitted that the skilled person would not consider this due to the more complex nature of the configuration and that the requirement for more material would also result in an increase in price.

The court agreed with Edwards that the technical effect of the distinguishing features is to provide a more reliable and durable valve and that the closest prior art also addressed this technical problem. The Court stated the solution provided in the prior art was structurally completely different, thus concluding that the prior art actually teaches away from the configuration anticipated by the claimed invention and as such the skilled person would have no motivation to modify the valve, as indicated by Meril.

Ultimately, the Court rejected Meril’s counterclaim for revocation and upheld the patent in the form maintained by the EPO’s Opposition Division concluding that the patent is valid and infringed.

In summary, claim language should not be interpreted more narrowly in view of the description and drawings, except for exceptional circumstances – such as when there is a clear and unambiguous indication that such a limitation was intended. Furthermore, the Local Division Munich has confirmed that the EPO’s PSA will serve as the primary approach for assessing inventive step at the UPC. Therefore, even though alternative approaches for assessing inventive step can still be applied, adopting the PSA may offer strategic advantages during patent prosecution and litigation.

Thank you